Drug & Food Allergy

Drug & Food Allergy

General Considerations

Some drugs are clearly more immunogenic than others, and

this can be reflected in the incidence of drug hypersensitivity. A partial list

of drugs frequently implicated in drug reactions includes B-lactam antibiotics,

sulfonamides, phenytoin, carbamazepine, allopurinol, muscle relaxants used for

general anesthesia, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antisera, and

antiarrhythmic agents. Many drugs can be associated with recognizable known

toxicities, drug interactions, or idiosyncratic reactions that are not

immune-mediated. These must be distinguished from true hypersensitivity

reactions because the prognosis and management differ. Some estimate that only

10% or less of adverse reactions to drugs are true hypersensitivity reactions.

Patients with multidrug hypersensitivity are quite rare, and those reporting

"allergies" to more than three distinct classes of drugs should be carefully

evaluated since intolerance to many of these drug classes may not be

immunologic.

Four foods account for 90% of food allergy in adults:

peanuts, tree nuts, fish, and shellfish. Food hypersensitivity must be

distinguished from food intolerance, which is more common and more variable in

terms of underlying mechanism. An example of food intolerance would be lactose

intolerance, which is due to an enzyme deficiency rather than an IgE-mediated

hypersensitivity.

Clinical Findings of Drug & Food Allergy

Symptoms and Signs

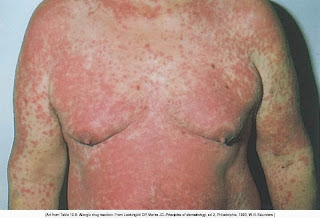

The development of symptoms and the nature of the adverse

drug reaction can suggest whether an immunologic process is responsible for

symptoms. Factors to consider include type of symptoms, history of previous drug

exposure, time of onset after starting the drug, presence of other systemic

involvement, coexisting illness, and concurrent drug use. In previously

sensitized individuals, immediate hypersensitivity is manifested by rapid

development of urticaria, angioedema, or anaphylaxis. Delayed onset of urticaria

accompanied by fever, arthralgias, and nephritis may indicate the development of

an immune complex-mediated disorder. Drug fever and Stevens-Johnson syndrome

probably act by immune hypersensitivity mechanisms. In genetically slow

acetylators and in AIDS patients with depleted hepatic glutathione levels, drugs

such as sulfamethoxazole are not rapidly excreted during drug metabolism. This

altered drug metabolism favors the generation of haptenated immunoreactive

metabolites as well as drug reactions, such as delayed morbilliform eruptions.

Other types of immune-mediated dermatologic drug reactions include lupus-like

syndromes caused by procainamide, isoniazid, phenytoin, or hydralazine. Drugs

that have been associated with the development of systemic or cutaneous

vasculitis include leukotriene receptor antagonists, allopurinol, phenytoin,

thiazides, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, furosemide, cimetidine, gold,

hydralazine, and many antibiotics (eg, penicillin, sulfonamides, quinolones, and

tetracycline). Cutaneous vasculitides are usually associated with fixed lesions,

with histologically-proven immune-complex involvement.

Food hypersensitivity is manifest by symptoms

consistent with IgE-mediated immediate hypersensitivity/anaphylaxis but

commonly is also accompanied by abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea.

More rarely, atopic dermatitis may be the sole clinical expression of

food allergy. The onset of allergic food reactions is rapid, usually within

minutes to a couple of hours of ingestion, and the reaction is usually quite

reproducible. Oral allergy syndrome is a self-limited form of fruit and

vegetable hypersensitivity, where symptoms are confined to the oropharynx. Due

to cross-reactivity between certain fruit and vegetable allergens and certain

seasonal pollens, ingestion of these foods causes a contact allergy with

pruritus of lips, tongue, and palate typically without other symptoms or signs

of systemic anaphylaxis. The most common cross-reacting foods and pollens are

apples and carrots, which cross-react with birch pollen; melons and bananas,

which cross-react with ragweed pollen. Many of these antigens involved in oral

allergy syndrome are heat labile and denature during cooking. Immunologic

cross-reactivity appears to also underlie the association of latex allergy and

hypersensitivity to avocado, banana, chestnut, kiwi, and papaya. Unlike the oral

allergy syndrome, however, systemic anaphylaxis upon ingestion of these foods

may develop in 35–50% of patients who are allergic to latex (so called

latex-fruit syndrome).

Laboratory Findings

Allergy testing

Allergy skin testing is only available for a limited number

of drugs (penicillin, insulin, streptokinase, chymopapain, heterologous serum),

since patients may react to the native drug as well as any metabolite that

covalently binds to native protein and becomes immunoreactive. Skin testing is

available for patients with suspected immediate hypersensitivity to penicillin

or  -lactam

antibiotics (see Infectious Diseases: Common Problems & Antimicrobial

Therapy). The degree of cross-reactivity between the cephalosporin antibiotics

and penicillins is uncertain. The incidence of IgE-mediated hypersensitivity

appears to be less than 5%. There appears to be no allergic cross-reactivity

between the monobactam antibiotics (aztreonam) and penicillin or other

-lactam

antibiotics (see Infectious Diseases: Common Problems & Antimicrobial

Therapy). The degree of cross-reactivity between the cephalosporin antibiotics

and penicillins is uncertain. The incidence of IgE-mediated hypersensitivity

appears to be less than 5%. There appears to be no allergic cross-reactivity

between the monobactam antibiotics (aztreonam) and penicillin or other  -lactam

antibiotics. A high degree of cross-reactivity exists between penicillin and the

carbapenem, imipenem, so this drug should be given to the penicillin-allergic

patient with the same degree of caution as if the patient were to receive

penicillin.

-lactam

antibiotics. A high degree of cross-reactivity exists between penicillin and the

carbapenem, imipenem, so this drug should be given to the penicillin-allergic

patient with the same degree of caution as if the patient were to receive

penicillin.

-lactam

antibiotics (see Infectious Diseases: Common Problems & Antimicrobial

Therapy). The degree of cross-reactivity between the cephalosporin antibiotics

and penicillins is uncertain. The incidence of IgE-mediated hypersensitivity

appears to be less than 5%. There appears to be no allergic cross-reactivity

between the monobactam antibiotics (aztreonam) and penicillin or other

-lactam

antibiotics (see Infectious Diseases: Common Problems & Antimicrobial

Therapy). The degree of cross-reactivity between the cephalosporin antibiotics

and penicillins is uncertain. The incidence of IgE-mediated hypersensitivity

appears to be less than 5%. There appears to be no allergic cross-reactivity

between the monobactam antibiotics (aztreonam) and penicillin or other  -lactam

antibiotics. A high degree of cross-reactivity exists between penicillin and the

carbapenem, imipenem, so this drug should be given to the penicillin-allergic

patient with the same degree of caution as if the patient were to receive

penicillin.

-lactam

antibiotics. A high degree of cross-reactivity exists between penicillin and the

carbapenem, imipenem, so this drug should be given to the penicillin-allergic

patient with the same degree of caution as if the patient were to receive

penicillin.

If the likelihood of immunologic reaction is low—based on

the history and the assessment of likely offending agents—and if no allergy

testing is available, judicious test dose challenges may be considered in a

monitored setting. If the likelihood of IgE-mediated reaction is significant,

these challenges are risky and rapid drug desensitization is indicated.

The gold standard for allergy food testing is skin-prick

testing with actual food items, but due to the inconvenience and potential risk

for systemic reactions, this form of testing is usually preceded by IgE RAST

testing or skin prick testing with commercially available extracts or both. Food

allergy testing must be interpreted within the context of the clinical picture,

since false-positive tests can occur.

Provocation tests

Occasionally, direct allergen challenge of the target organ

or tissue under controlled conditions is required for definitive diagnosis. Such

challenges may be bronchial, nasal, conjunctival, oral, or cutaneous. A positive

test confirms that the test substance can cause the reaction, but it does not

prove that an immunologic mechanism is responsible.

In most cases of suspected allergy to a food or drug,

placebo-controlled oral challenge is the definitive test. To be considered a

positive result, the reported clinical findings must be reproduced during

provocation testing. A blinded provocation test may be preceded by an open

challenge (no placebo control), which, if negative, negates the necessity for

logistically difficult blinded challenge. Freeze-dried foods in large opaque

capsules provide a sufficient dose of allergen for testing. This should not be

done in patients with suspected food- or drug-induced anaphylaxis.

Treatment

For IgE-mediated drug hypersensitivity, acute rapid

desensitization may allow administration of a drug if there is no suitable

alternative treatment regimen. This procedure carries a significant risk and

should be undertaken in an intensively monitored setting. This is accomplished

by a course of oral or parenteral doses starting with extremely low doses

(dilutions of 1 x 10–6 or 1 x

10–5 units) and increasing to the full dose over a period of hours.

IgE-mediated reactivity diminishes during the course of this desensitization,

creating a temporary drug-specific refractory state. During the refractory

period, skin histamine responsiveness is maintained, and mast cells may be

activated by other stimuli but the patient may receive the desired drug with a

very low risk of anaphylaxis. Acute rapid desensitization may work through

cellular mechanisms different from those involved in standard injection

immunotherapy, and the refractory period is maintained only throughout the

course of uninterrupted therapy.

Various slow desensitization protocols have been developed

for patients suffering from late-appearing morbilliform eruptions (eg, AIDS

patients with sulfamethoxazole-induced dermatitis). These eruptions are not

IgE-mediated, and the slow reintroduction of drug allows for less haptenation

during sulfonamide metabolism with generation of less immunoreactive drug

metabolites. This form of desensitization is distinct from rapid desensitization

of IgE-mediated drug allergy. Desensitization for non–IgE-mediated drug

reactions has been successful for aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs,

and allopurinol.

Any history or finding consistent with toxic epidermal

necrolysis or Stevens-Johnson syndrome would be an absolute contraindication for

drug readministration.

For any proven food hypersensitivity, strict avoidance is

the only rational recommendation. Patients should also be provided with an

epinephrine autoinjector (Epi-pen) if indicated.

I hope, Drug & Food Allergy article be usefull for your.

Recources:

Current Medical Diagnosis & Treatment 2008

Stephen J. McPhee, Maxine A. Papadakis, and Lawrence M. Tierney, Jr., Eds. Ralph Gonzales, Roni Zeiger, Online Eds.

Current Medical Diagnosis & Treatment 2008

Stephen J. McPhee, Maxine A. Papadakis, and Lawrence M. Tierney, Jr., Eds. Ralph Gonzales, Roni Zeiger, Online Eds.